Give Yourself Some House Money

I’ve been blown away by the overwhelming feedback I received on last week’s piece—in the comments, in my inbox, and even via text message. It was validating that so many of you replied to my late-night borderline rant with words of wisdom and empathy. The most common bit of feedback? Take a break.

So instead of writing a piece this week, I’m introducing you to another member of the Wayfinder crew, Shivani Shah, or Shiv as we call her. Below is one of my favorite pieces of hers.

Before you go, subscribe to her newsletter, Stories by Shiv:

“Everyone wants an exciting life, but most people are afraid to take the bull by the horns. So they take an easy option for an exciting life. They live their excitement through other people. By aligning themselves with famous rebels, a little bit of glamor rubs off on them. They imagine they’re like John Lennon, Ernest Hemingway, George Best, Liam Gallagher, Lenny Bruce, Janis Joplin, Damien Herst, Andy Warhol, etc. The difference being, these people when faced with a decision took the outrageous one, not knowing where it might lead them, but knowing that the safe decision had danger written all over it.”

Paul Arden

I’ve been so tied to the idea that there are tradeoffs for everything. In an effort to not make the “wrong” trade off, I’ve generally limited myself to activities that present the least risk, not recognizing that those very activities are in fact the riskiest for the simple fact that I’m not acting from a place of first principles.

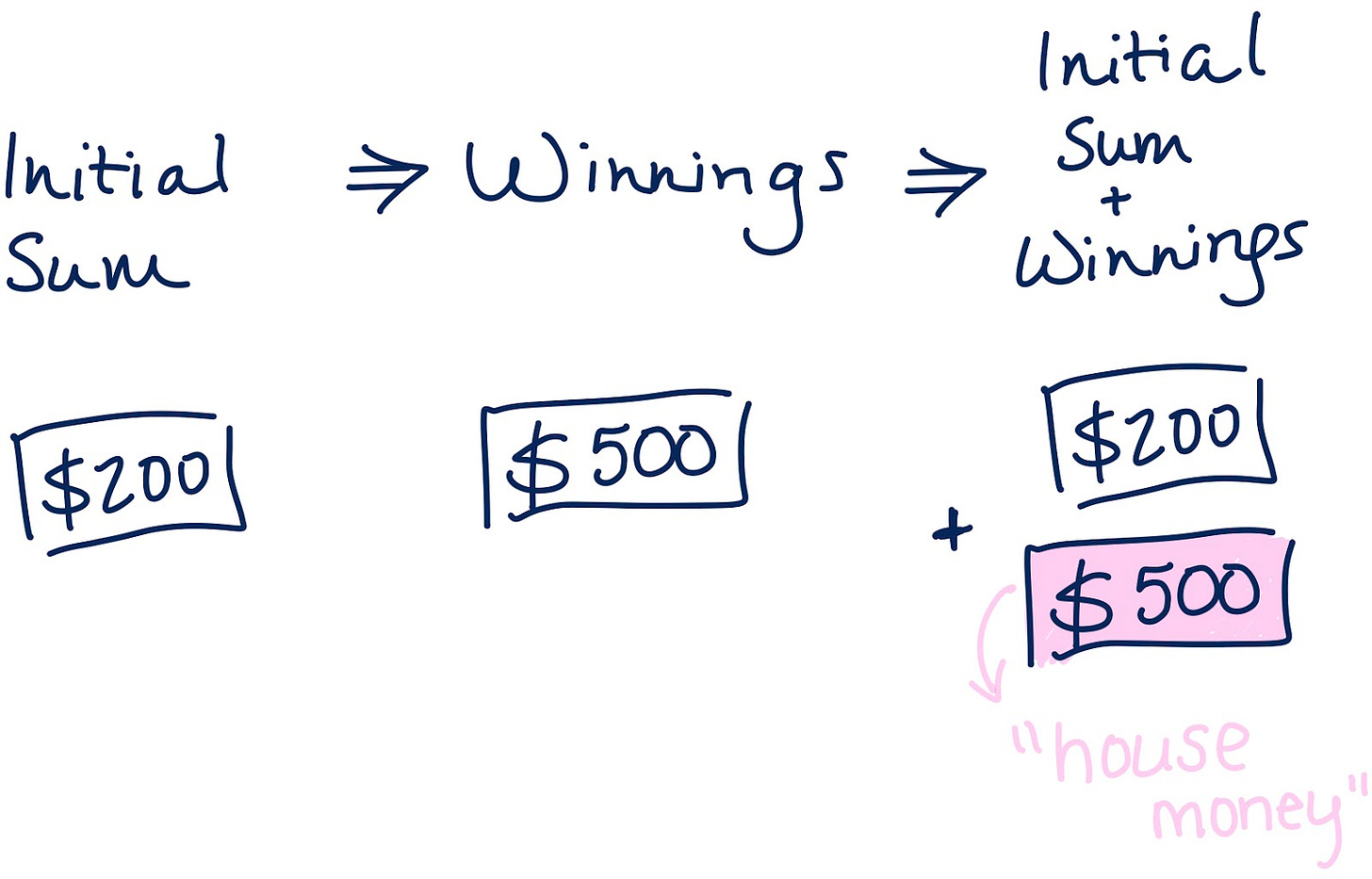

House Money

Have you heard of the concept of house money? I hadn’t either until an ex-pro poker player explained it to me. Playing with house money is a cognitive bias in gambling where players are willing to take greater risk with the money they’ve won than the initial sum they started out with. It’s as if their winnings don’t belong to them, but still belong to the house (AKA the casino).

The same bias exists outside of casinos too. Think: gift cards given to you or returns on your initial investment when the market does well.

We are looser with house money, gift cards, and gains than we are with our own, hard-earned cash. House money came easily, so we’re open to letting it go easily too. Of course, this is illogical, as money is just money — regardless of where it comes from.

It doesn’t matter if you win a dollar or if you earn a dollar. The literal value of that dollar is the same, while the assigned value (and resulting risk tolerance) can differ.

But is there an upside to this cognitive flaw? I think so. It allows us to take greater risk than we would otherwise, opening the possibility of greater reward.

What if we applied this same bias to a different, more important currency? What if we applied it to time?

Time Through the Lens of House Money

Let’s say you knew what age you would die. Call it 85.

Cause of death? Unknown.

Happy or sad? Unknown.

All we know is that you have from now to 85 to live. For me, that would be another 58 years.

But then, let’s say you were given an incremental year right now. Would you live that year differently? Like, a gap year or a sabbatical.

I’d be jazzed at the idea of this extra time. I’d spend it exploring things that would make me feel the most alive: learning how to sail, surfing down the coast of Portugal, making a film, writing a book, etc. — the things that my dreams are made of. Exploring for the sake of exploring.

Maybe your dreams look different from mine, but if given an extra year, I have a hard time believing that you would use that time to accumulate wealth or status. In this scenario, the best use of time would be to spend it on the kinds of activities that many of us wouldn’t let ourselves commit to with our “normal” time.

Alas — no one is giving me an incremental year in life. I don’t even know that a life until 85 is in the cards for me. But if spending time in the ways I’ve described is the best way to feel alive, why aren’t I doing those things right now? What’s stopping me?

Time

Since time isn’t something we can “win” more of, we guard it closely; rarely taking too great a risk on how we spend it. And what’s the least risky way to spend our time? To use it in the most productive way so that we never feel like we’ve wasted this consistently depleting currency. In our society, a productive use of time generally follows the pattern of money as a proxy for success:

We’re told to do well in school so that we can get into a solid university in order study something that will allow us to be hired in a lucrative position, and when we get bored, it’s not a problem, because we can just go back to school to get a masters so that we can make even more money but pausing this cycle to figure out what we actually care about is not even an option that we entertain, because taking that kind of risk would hinder our progress in this race towards some arbitrary finish line that we’ve been told to run towards.

If this intentionally-never-ending-rat-race-sounding-run-on-sentence resonated, read on.

Much of the time we spend in adolescence and early adulthood feels like a single effort to point our arrow at some fancy corner office in a tall building, rarely (if ever) stopping to examine if this outcome will truly make us feel like we haven’t, in fact, wasted our time.

In this way, we think we’re not being risky with how we’re spending our time. But the subtext in this script is the inherent risk involved in the blind pursuit of “success”, where the goals are defined by anyone besides yourself.

Eliminating Wonder

We’re spending our precious currency of time on things we might not even value. So we continue optimizing for money, productivity, and success to the point where we are willing to give up time in exchange for it, regardless of whether or not these things are earned as a product of something that truly speaks to us.

This is because collecting these things is a socially acceptable indicator of success, while collecting experiences is not.

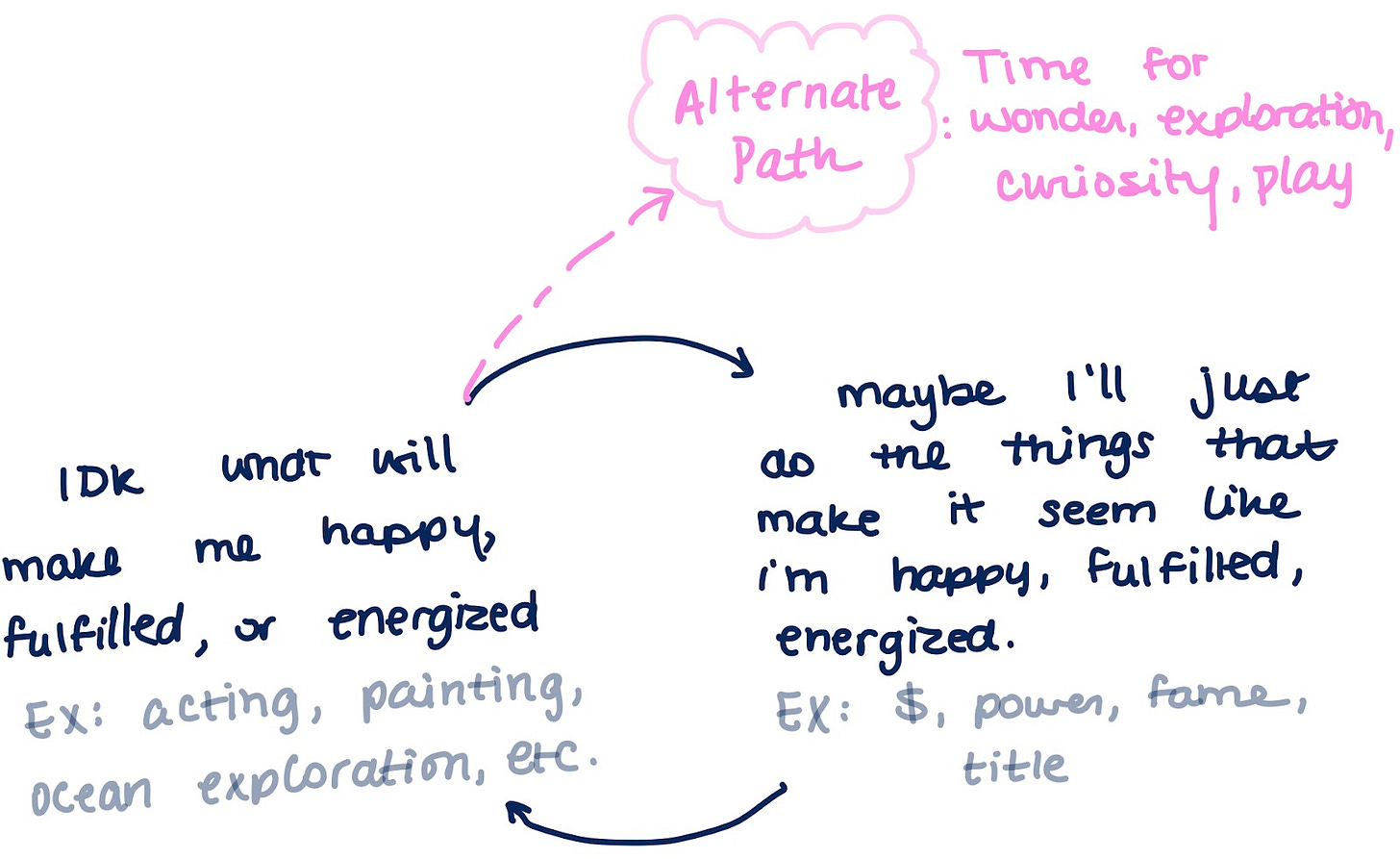

When we don’t know what will make us happy, we go on thinking, “Well, at least I’ll have money and a strong resume to fall back on.” We’d rather give up our time in exchange for a ~potentially~ valuable currency than spending it on the unknown. Exploration is not an option, because exploring for its own sake isn’t considered productive enough in our society.

What this creates is a systematic erasure of wonder and curiosity from our lives. It destroys our sense of play and it’s highly unnatural.

By definition, play must be purposeless in order to be considered play. It requires comfort with uncertainty, which directly threatens social and financial progress. In order to eliminate such risk, we are taught to avoid ambiguity and replace it with monochromatic formulas of success masking as happiness.

But avoiding ambiguity is the antithesis of exploration. Optimizing for success in this way ignores our biological need for play.

“Expanding Your Universe”

I have found myself falling into the productivity and success trap. But I’m starting to realize that wonder for wonder’s sake is a better use of time than productivity for productivity’s sake.

Hindsight is 20/20 when I think about how I got to this place. It comes down to an obsession with success and a fear of failure, both of which I let others define on my behalf.

In chatting with the Stories by Shiv community, I sense that a lot of us feel this way. I found solace in executive coach Liz Tran’s perspective on what to do when sitting with this feeling of uncertainty. She advises to “expand your universe”.

Meaning, to embrace the uncertainty and lean into paths we don’t know about yet. Since we don’t know what we don’t know, the only way to expand your universe is through play, exploration, and curiosity.

If that sounds ambiguous, it is. And that’s the point.

Expanding your universe doesn’t have to be overwhelmingly grand. It can mean reading a book from a genre you don’t touch, watching an international film, taking a dance class, visiting a museum, etc. Small steps in spaces of discomfort can breed an outsized impact on our understanding of the world.

When we’re so sure of ourselves, we b-line toward a certain outcome. When we reach that outcome, and it doesn’t yield the same feeling we anticipated, it’s easy to question everything — all of our actions and decisions that brought us to this point.

But for most of us, meandering and questioning our own beliefs is necessary.

If we truly had it all as figured out as we originally thought, what would be the fun in that?

//

In reality, none of us know how much time we have. So, wouldn’t it serve us all well to treat a year (or two or five) as if it were house money? A little extra. Something we didn’t earn, but got to spend anyway.

Give Yourself House Money,

Shiv

For more Stories by Shiv content, you can find me on Twitter, Instagram, and even TikTok.

I hope you liked Shiv’s piece as much as I did. Don’t forget to subscribe to her newsletter:

If you liked this piece, please let me (and Shiv) know by giving the heart button below a tap.

"We’re told to do well in school so that we can get into a solid university in order study something that will allow us to be hired in a lucrative position, and when we get bored, it’s not a problem, because we can just go back to school to get a masters..."

Whenever I find myself considering going back to school, it's always been from a place of fear rather than a place of wonder.

Excellent work Shiv

This reminds me of the many views and quotes the Stoic's have on the subject of death. I've been pondering a lot of these views/quotes lately that teach how we should put up mental boundaries around the things that keep us from living life to the fullest. Worrying about money, that job promotion, successes that we cannot control, and even death keeps us from wondering and exploring and even enjoying life.

This also makes me think of how many things we say "yes" to in life that should really be big fat "NO's"!!

Thanks, Shiv, for this!!